This paper is part of a thesis Written by Renaldo C. McKenzie in partial fulfillment of his Master of Philosophy in Liberal Arts at the University of Pennsylvania, published in 2011, updated with an extended conclusion April 2022. This paper is published as part of a series of paper that will be presented as Jamaica celebrates sixty (60) years of Independence this year beginning August 6, 2022. VP Kamala Harris and the PM of Jamaica Andrew Holness met recently to discuss how the US can continue to support and strengthen Jamaica’s goals towards realizing their goals of sustainable development especially in the area of building their human capital.

Abstract:

This paper examines how extensive and effective Jamaica’s, and the United States social security program is particularly, social policy on poverty reduction. We will explore the Program of Advancement through Health and Education (PATH) aimed at providing unemployment cash assistance to the poor and unemployed. This includes making comparisons with similar programs (TANF) in the United States. Uppermost in our consideration is the impact of neoliberal globalization on Jamaica’s and vulnerable people’s ability to provide welfare to its citizens and or to create a path towards sustainable development including poverty reduction and increased distributional equity

INTRODUCTION

The aim of Social Assistance is to help the poor cope with the risks of poverty in a global neoliberal society, by redistributing the wealth created in the market. The extent of this assistance does not necessarily alleviate poverty or create distributional equity. Jamaica and the United States, former British colonies, have been experimenting with income redistribution through social welfare to reduce poverty and inequality since the British Poor Laws over 200 years ago. Despite consistent reforms to improve these welfare initiatives poverty and inequality are still at unacceptable levels especially among the most vulnerable. In 1996 The United States dismantled its AFDC and created a new social assistance program, TANF, to reduce needy families’ dependence by forcing them to work albeit low-wage dependent jobs. Similarly, Jamaica reformed its social safety net by conflating its 45 programs into a new PATH program to provide better coverage and assistance and to empower the poor. Notwithstanding this wave of initiatives, poverty ricocheted to higher levels and is rising, while income distribution is far more unequal.

Therefore, this study compares Jamaica’s social assistance program, PATH (Program for the Advancement through Health and Education) to the United States TANF (Temporary Assistance to Needy Families). This comparison is done by measuring the extent to which these welfare programs redistribute income to alleviate poverty and reduce income inequality. Of course, we have already said from the outset, that such programs by their very definition are not necessarily design to prevent or lift people out of poverty but are merely a coping mechanism to help the poor maintain a minimal or less than basic standard of living. Hence it will be interesting to ascertain from this research whether this anecdotal observation holds true. The redistributive power transfers in the two countries will be measured by their coverage, size, absolute incidence and simulated impacts on poverty and inequality and by their distributional characteristic.

I find that social assistance in these countries can be effective instruments to redistribute income and empower the poor. Yet they have not managed to do so as effectively due to political reasons based in ideologies, administrative mal-practice and bungling, shortfalls in governmental revenues and the need for society to retain a set of “lumpen proletariats” to provide cheap or slave labor. Further, the redistributive impacts from social assistance are more limited and even regressive in the US than Jamaica. This progressivity derives from a design factor which truncates coverage due to requirement of membership in formal labor markets. TANF covers only 40% of eligible poor (which represents a 50% reduction in social assistance coverage since 1996) and excludes 80% of those earning below poverty line. On the other hand, PATH covers 59.6% of those in the lowest quintiles up from 30%. Nevertheless, it too excludes a large proportion of the most eligible poor (40.6%). Hence the conclusion is that both countries’ welfare programs are ineffective in assuaging poverty. Governments should therefore reconsider these programs or at least strengthen their design. However, without international aide, Jamaica’s spiraling debt and development levels prevent them from effectively redistributing the wealth (which is scarcely limited). The United States are in a better position to produce the kind of programs that will see marked difference in the standard of living of its poor. But unless a more equitable and just distribution of the wealth is vigorously pursued by US and Jamaica, I’m afraid these programs will continue to meet only the basic or less than basic needs of the poor.

JAMAICA’S SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CONTEXT

Colonialism and Neo-liberal globalization have severely debilitated Jamaica’s ability to effectively maintain a comfortable living standard for the poor. Independence from Britain in 1962 and the end of their relationship with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in 1996 have not unhinged Jamaica’s dependence on the global north. Jamaica was forced to liberalize and privatize its economy after it could not meet its financial obligations. Beyond the 70’s government continued to play a strong role in providing as far as possible for the welfare of its most vulnerable people.

Historically, Jamaica was stratified along racial/class lines stemming from the plantation system. According to Lundy, class structure is characterized by mal distribution of wealth and there is a correlation between wealth and whiteness (1999, p. viii). However, this classification grossly underestimates the growing middle-class which grew from 25% in 1961 to 37% in 1991. Hence, class is now based on occupation-status as well as race. As Jamaica moved towards political independence in the 1960s, Jamaica experienced significant economic growth. However, those at the bottom quintiles were divorced from this growth as poverty recorded a high of over 30%. This led to massive migration to Europe and North America by the poor as there were no effective social security programs to insure against the effects of poverty. Those who remained, infected by Cuba’s Fidel Castro and the socialist imperatives in the region, commandeered a political revolution that birth Jamaica’s socialist agenda in the 1970’s which gave rise to democratic socialism. Hence, the wealth was redistributed as the government led a social-economic policy of distributional equity. The welfare regime transitioned to a conservative, corporatist system in the 1950’s and 60’s to one that resembled more the Universal or social-democratic regime. As a reaction to this ideological move which also affected the profit margins of the wealthy and democratic dominance in the region, capitalists fled the island. Investment and foreign Aid from US and the UK dried up. The issue was compounded by the severe oil crisis of the 70’s and the neglect of the market and infrastructural development that severely affected government’s overall revenues and ability to maintain government spending.

So, by the 1980’s Democratic-Socialism was abandoned so as to garner international financial assistance to alleviate economic disequilibrium and balance of payments deficits. The government was forced to commodify its welfare system and liberalize its economy through Structural Adjustment to facilitate neoliberal globalization. However, economic restructuring towards a market economy was slow and haphazard as government continued (though decreasingly) to provide social security. While this restructuring created a burgeoning and active middle-class and pushed poverty down, this was on the backs of the poor who had remained and fallen into abject poverty. Further, unemployment and overall standard of living worsened among rural residents, whose farming goods couldn’t compete with cheaper imported products, experienced declines in their industry, and migrated to urban areas in unsavory living conditions.

By the 1990’s informal employment and the underground economy of drugs and gang violence provided the best alternative means of survival within a policy that was increasingly neglecting the poor. This placed tremendous burden on the community and the family which lacked the access to maintain a basic and comfortable standard of living. “Dons” (area leaders and criminal kingpins) provided the social safety net in communities that were largely neglected by a weakened state that was becoming less involved given global pressures to liberalize and marketize. The family, church and community groups play aided by international donor agencies picked up the lax by the state, thereby playing an integral role in mitigating the social risks in the Jamaican society; so that the experience of risks have not been as traumatizing and militating. In fact, one writer asserted that many Jamaicans who live in poverty and are vulnerable to risks are ignorant of this given this strong support-network. However, Jamaica’s standard of living amongst the poor remains a sore issue which provided an impetus to the GOJ to reform and improves its welfare program to expand its coverage and reach to the poor.

”’The Effect of Global Recession on Jamaica and the US”’

During most of the 1990s, the Jamaican economy experienced low or negative growth. In 1996, a crisis in the financial sector exacerbated matters when the solvency of several insurance companies and other domestic financial institutions emerged as an issue. While Jamaica has made remarkable progress in some social sectors (for example in 1990 poverty rate decreased from 28 percent in 1990 to 17 percent in 1999; the upward trend in some social indicators is likely to be temporary unless the economy improves. But this is likely an insurmountable task given the effect of globalization and the recession on the Jamaican economy. This resulted in significant job-losses, salary cuts, rising inflation, devaluation in the Jamaican dollar against the US dollar, rising unemployment and massive reduction in main income-generating sectors – remittances, tourism, bauxite and agriculture which adversely affected government’s spending and their ability to grow the economy and effectively redistribute the wealth to the poor. In addition, focus group research conducted in Jamaica by the World Bank in 1999 found “significant decreases in the well-being of the poorest individuals over the last ten years” and, in rural areas, “an emerging category of severely poor households, often including the elderly” (The World Bank 2001b, p. 6).

However, unemployment has declined from 15% in 1990 to 10.6% in 2008. This decrease is partly due to the growth of the informal sector from an estimated 28% of GDP in 1989 to an estimated 43% in 2001, probably one of the several contributors to a significant reduction in poverty levels. But this is unlikely to be sustained as middle-class income has declined due higher levels of inflation and a flat growth rate. Coupled with a reliance on imports particularly oil, food and consumer goods, this makes the Jamaican economy acutely vulnerable to exogenous shocks. In light of this situation, the challenge for GOJ was to prevent a reversal in the significant declines in poverty witnessed in the 1990s and to ensure that the poor were adequately protected. But let us look us look closely at the mature of poverty and inequality in Jamaica as affected

‘Poverty and Income Inequality in Jamaica’

In fact, exacerbated by the global recession, a major force behind the development of PATH is the nature of poverty in Jamaica and its relationship to education and health care for instance, poverty is concentrated among the young and the old, with almost half of the poor younger than 18 years of age and another 10 percent over age 65 (Blank 2001). Secondly, in rural areas, with nearly 80 percent of the poor living in rural areas and less than 10 percent living in the Kingston Metropolitan Area (The World Bank 1999). Thirdly, among female-headed households, with 66 percent of poor households headed by women, although women head only 44 percent of all households (Blank 2001). And fourthly, among larger families, with 40 percent of poor families consisting of six or more members (The World Bank 2001c). In addition, Jamaica’s comparatively favorable social indicators mask a significant lack of access to education, especially among the poor. Although poor children are typically enrolled in school, they sometimes do not attend regularly. Poor families tend to attribute erratic attendance to “money problems.” Indeed, the World Bank found that a lack of money has prevented parents from sending their children to school and providing them with food, clothing, and shelter. Poverty is related not only to education but also to the quality of and access to health care. Also, poverty poses a barrier to health care, especially in rural areas.

Moreover, from 1971 – 1993, the top 20% experienced a sharp fall in their incomes, while the bottom income groups all had increases in their income. The Gini-coefficient which measures income inequality fell from 0.53 to 0.362 which suggests that Jamaica had greater equality as the GOJ maintained relatively strong state intervention. However, due to the acceleration of neo-liberalism in the decades of the 1990’s and 2000’s, marked by greater financial deregulation and market reform; the economy underwent a financial collapse and an economic recession that disproportionately affected the poor and working-class. Hence, the poor and working class experienced a sharp fall in their incomes while the incomes of the richest remained the same or increased thereby pushing the P/R ratio from 42.6% to 53.5%.

”’The Comparative Effect of the Global Recession on the US”’

On the other hand, the United States, unlike Jamaica, is highly diversified and developed with annual per capita incomes and domestic production that more than quadruple Jamaica’s rates. Yet, globalization and the current recession have produced similar hardships among their most vulnerable peoples, with rising poverty and extremely high unemployment. The current global recession followed a disappointing economic recovery that started at the end of 2001 and culminated in 2010. That recovery marked the first time on record that poverty and the incomes of typical working-age households worsened despite six years of economic growth. The share of Americans in poverty climbed from 11.7 percent in 2001 to 15.7 percent in 2010 and median household income declined 3.6% reaching its lowest point since 1997. The recession has been characterized not only by high levels of unemployment, but also by the speed at which the ranks of the unemployed swelled. Between the start of the recession in December 2007 and January 2010, the unemployment rate more than doubled, from 4.9 percent to 9.7 percent.

”’THE D/EVOLUTION OF SOCIAL ASSISTANCE”’

The Rationale and Evolutionary Development of PATH

Before the development of PATH in 2001, the GOJ since the mid-1930’s provided minimally for the poor. However,, since Jamaica’s independence in 1962, the GOJ financed 45 safety net programs through 12 ministries/department of government. However, the effectiveness of these programs was perceived to be low. For instance, the World Bank recently found that the majority of these programs do not adequately serve the poor (The World Bank 2001c). Nevertheless, even though some of the programs target the poor, they fail to reach a significant share of the affected population. In addition, other programs are not designed to target the poor at all (as is the case for most of the labor market programs).

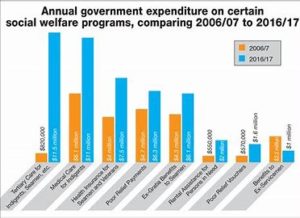

In 2001 PATH was created as a means-tested program designed to replace three major income support program that provided cash or in-kind assistance (the Food Stamps Program, the Poor Relief Program, and the Public Assistance Program) to the poor. This reflected a new approach that combines social assistance with the accumulation of human capital, which underscored a movement towards defamilialisation and further decommodification of the welfare system. The PATH is funded in part by the World Bank and the GOJ who also administers and monitors the program through its Ministry of Labor and Social Security (MLSS). The program is intended to fight poverty in the present through monetary transfers and to reduce poverty in the future by encouraging poor households to invest in the health and education of their children.

PATH identifies poor households through a scoring formula that ranks households from poorest to best off. Households scoring below a predetermined threshold level are eligible for program benefits. PATH is organized around two components. Firstly, Child assistance grants which provide health and education grants for eligible poor children through age 17. The average monthly benefit per child receiving a health or education grant in 2005 was about US$6.50 which is only 20% of the minimum standard of living not barely enough to survive . Secondly, Social assistance grants to adults that provide grants to poor pregnant or lactating mothers, elderly poor (over age 65), and poor, disabled, and destitute adults under age 65. Initially, the receipt of benefits was conditioned on adults making regular health clinic visits. However, this changed shortly after the program was launched and benefits for adults are no longer conditional.

Similarly, in the United States, Congress created TANF as a means-tested federally funded, state-administered safety-net program to help support low-income individuals and families to meet their basic needs. Some cannot find employment. Others can only find part-time work or earn wages far below what they need to cover their basic expenses. Still others are facing short or long-term personal or family challenge that makes work or steady work infeasible. In 1996 TANF replaced the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, which provided monthly cash grants to families with children. A key feature of TANF is that it is a fixed block grant that is provided to the states, which then have broad flexibility to decide what benefits to offer and under what conditions, consistent with the four TANF purposes set forth in the law. States have a maintenance-of-effort (MOE) requirement that compels them to continue to spend at least 75 percent of the funds they were spending in their AFDC and related work programs as of 1994 on one of the TANF purposes. Over time, states have spent a declining share of their TANF block grant and MOE funds on basic monthly cash assistance for families in need; in fiscal year 2008, they spent only 30 percent of their $30 billion in TANF and MOE dollars for this purpose. States used the remaining funds to provide child care, other work support and employment programs, transportation, and other services to families with children.

Typical TANF programs provide a monthly cash grant on an electronic benefit card to program participants, most of whom are required to participate in select work activities as a condition of initially receiving or continuing to receive cash assistance (which like Jamaica covers only 20% of the minimum needed to meet the basic standard of living).

But this new approach characterizes Americans conservative ideology which promotes a new protestant ethic of individualism, self-interest and neo-liberalism. Traditionally, the US has loathed big government and any kind of social program that involves socialism. Poverty and inequality is an individualistic responsible stemming from the “blame the victim” mentality. Hence, the profits are privatized and risks socialized, within a de-commodified political welfare regime that promotes and protects capitalist wealth and at the expense of external risks borne by the losers. Therefore, overtime TANF has served a decreasing share of eligible families. In 1995, AFDC served 84 percent of all eligible families; in 2005, TANF served only 40 percent of all eligible families. As a result, TANF has become less effective over time at reducing deep poverty (defined as having family income below 50 percent of the poverty line). We will see this clearly when we examine the redistribution outcome of TANF in the next chapter.

”’REDISTRIBUTION OUTCOMES OF PATH AND TANF: BENEFIT TARGETING”’

ARE PATH PARTICIPANTS POOR?

Most PATH participants are poor. About three of every five PATH participants have consumption levels below the poverty line. By contrast, the overall poverty rate in Jamaica at the beginning of the program was about 20 percent (one of five). About four of every five PATH participants fall into the bottom two quintiles of the consumption distribution, which means they are among the lowest 40 percent of Jamaican households in terms of adult-equivalent consumption levels. Among those participants who are poor, about half are in particularly dire circumstances. About one of every four participants is in extreme poverty, which implies that while most participants are poor or close to being poor, a small fraction of PATH participants seem to be relatively well off. About 6 percent of households fall into the top two quintiles of the consumption distribution. About 17 percent of PATH participants have consumption levels greater than 1.5 times the poverty line, and about 6 percent have levels greater than twice the poverty line.

Therefore, PATH has been relatively successful at targeting its benefits to the Island’s poorest households. Specifically, 59.6 percent of benefits were found to go to the poorest quintile of the population. However, this excludes 40 percent of the poorest. Comparisons made to TANF in the US suggest that this figure compares favorably with results that have been attained elsewhere.

TO WHAT EXTENT HAS PATH REACHED THE POOR?

It is useful to assess the extent to which PATH was able to reach poor households in Jamaica by comparing its coverage and reach to other social assistance programs in Jamaica and the US (TANF). An indicator often used to quantify coverage is the coverage rate – the percentage of poor Jamaican households served by PATH. In 2002, the overall estimated poverty rate in Jamaica was about 20 percent. With Jamaica’s population at approximately 2.6 million, the total number of Jamaicans living in poverty is 520,000. As noted earlier, the current number of beneficiaries receiving PATH benefits in a typical period is approximately180,000 and 59, percent of these enrollees are poor. Thus PATH is currently reaching approximately 106,000 poor beneficiaries. Overall, therefore, the program’s coverage rate is approximately 20 percent (106,000/520,000). Moreover, poverty grew to a total of 445, 500 (16.5%) and the assistance from government grew by 60 percent during the period so that 70 percent (315, 000) of the persons in poverty received assistance. This therefore represents an increase in benefit targeting.

In addition, PATH has been effective at accomplishing its objective of encouraging households to send their children to school with greater regularity. PATH has also been successful in meeting its objective of increasing the use of preventive health care for children in PATH families.

While PATH has been successful at increasing school attendance and preventive health visits, there is no evidence that it was able to affect longer-term outcomes such as grades, advancement to next grade, or health care status. There are problems with implementation. And the targeting of benefits may still be improved, however as persons who were not deserving, received PATH benefits while certain other households were turned down by PATH, even though their need for assistance seemed very great. Moreover, the coverage is still limited and excludes a large portion of the population who are poor.

COMPARISONS WITH OTHER TRANSFER PROGRAMMES IN JAMAICA

Relative to other social programs in Jamaica, PATH’s targeting performance seems to be good. In particular, PATH has achieved much better targeting than Food Stamps, one of the main programs for which it was to provide a substitute. About 59 percent of PATH beneficiaries fall into the bottom quintile as compared with 36 percent of Food Stamp participants. In addition, about four of every five PATH beneficiaries fall into the bottom two quintiles of the consumption distribution as compared with only about three in five Food Stamp participants. In addition, 6 percent of PATH beneficiaries fall into the top two quintiles as compared with 18 percent of Food Stamp participants. Overall, PATH seems to be doing a much better job in targeting the poor than Food Stamps. In targeting the poor, PATH also seems to be doing as well as or better than other Jamaican assistance program.

HOW DOES PATH COMPARE WITH TANF?

The effectiveness of PATH in redistributing the wealth must also be compared against TANF’S overall coverage and target. In addition, it is interesting to ascertain how TANF performs in comparison with other welfare programs in the US such as the food stamps program. As notes earlier, PATH is more effective in targeting the poor and covers more poor people. But this is not the case in the US with TANF. Unlike food stamps, which are available to nearly all low-income individuals, only families with children are eligible for TANF benefits. In 1995, AFDC lifted 2.2 million children out of deep poverty; in 2005, TANF lifted only 650,000 children out of deep poverty – fewer than food stamps and other means-tested benefits. Still, TANF remains an important component of the safety net, as it is one of the few programs that provide cash assistance to non-working families to help them meet their basic expenses.

TANF Cash Assistance Programs Have Responded Unevenly

In most states, TANF cash assistance programs have lagged far behind the Food Stamp Program in their responsiveness to the recession and rising poverty. Nationally, the total number of families with children receiving cash assistance has increased by just 10 percent since the beginning of the recession.

Since TANF’s creation, states have focused on reducing their TANF caseloads for a variety of reasons – fiscal, ideological, and as a public measure of effective performance – and even during the current economic downturn, they have been slow to shift away from this emphasis. Many states have policies and procedures in place that make it difficult both for eligible applicants to obtain benefits and for recipients to continue receiving benefits even if they remain eligible. Some states require applicants to participate in work activities for a period of time before they can qualify for aid, but some families may be in crisis and have difficulty meeting these requirements until they begin to receive help in meeting basic needs. States have continued to impose these work requirements even during the economic downturn. Many states have eased their enrollment processes for food stamps and Medicaid but not extended these improvements to TANF; others continue to actively discourage TANF applicants. In some cases, families in need may not pursue TANF because of stigma, erroneous information about eligibility, time limits, or other reasons.

CONCLUSION

A. So how effective is PATH and TANF in Targeting the Poor?”

So how effective is PATH and TANF in redistributing the wealth to the poor so as to assist them in coping with this uneven global economy that has largely excluded them? And which is more effective at targeting the poor? What lessons can both countries learn to properly treat the problem of poverty and income inequality? We have argued throughout this paper that poverty and income inequality exists and are worsening in spite of these programs. Reforms in Jamaica have widened the social safety net to catch the poor and ameliorate the risks. But still the efforts are insignificant as the assistance is a far cry from what is necessary to meet the poor’s basic and minimum standard of living. But when compared to the US TANF program, Jamaica seems to be way ahead, disadvantaged only by their slow economic growth and dependence on foreign aid. The US has reformed its social assistance program which has effectively ended social welfare and its means-tested work requirement makes poor people vulnerable to slave and cheap labor. Jamaica has relaxed its means test and conditional requirements making it easier for the most eligible to benefit from the program. This attitude stems from a political climate that underscores an integrated and social approach to living. However, the US is highly liberal and individualistic and opposes socialism. The risks are socialized minimally and individualized optimally. This exposes the vulnerable to wage-dependent labor which propagates a cycle of poverty and inequality. America should learn from Jamaica, but more so from the Scandinavian countries that are highly de-commodified and are benefitting from a surplus, high employment, skilled labor high wages and growth that such a regime brings. These countries have effectively redistributed the wealth so that there is very little poverty and inequality.

Jamaica is aiming to do so. But is limited by its low level of development and pressure from the neo-liberals to reduce government intervention in the market so that they can continue to profit from the openness and a desperate group all too willing to work at and for anything.

Indeed, poverty and income inequality have increased despite these welfare schemes, so none is very effective in redistributing wealth to the poor. But the US is in a better position to do so because of its level of development and economic prowess. Yet TANF unlike PATH is a social assistance program that lacks the human capital component that is necessary to empower the poor marketability. Jamaica’s PATH is aiming to improve the living standard of the poor through increasing their human capital. This is a best practice which may be applied to the TANF program that has MOE (maintenance- of- effort). Jamaica’s program is almost more effective, but their openness, dependence and debt make it difficult to provide universal coverage or to improve the program. They have benefitted tremendously from foreign aid which bore at least 50% of the cost of providing welfare.

Nevertheless, social assistance in these countries can be effective instruments to redistribute income and empower the poor. Yet frequently they have not managed to do so as effectively and efficiently. TANF program has served a decreasing share of eligible families and both TANF AND PATH coverage rate excludes a significant number of poor people. On the other hand, Jamaica’s PATH program, which started in 2001, has not only served an increasing number of poor families, but helped to augment its human capital as the program unlike the US does not have a work requirement but an education and health requirement. Hence both Jamaica and the US welfare social assistance programs are ineffective in curbing or alleviating poverty. Governments should therefore reconsider these programs or at least strengthen their design. They could also look to targeting mechanisms that have impressive rewards wherever this is found. But unless a more equitable and just distribution of the wealth is vigorously pursued, I’m afraid these programs will continue to meet only the basic or less than basic needs of the poor.

Finally, at the end of the day, Smith asserted that the most critical driver of poverty reduction is whether Caribbean countries create the conditions for producing relatively sound and sustainable economic growth going forward.

“Specifically, to Jamaica, I think a big part of the problem has to do with the fact that for the last 30 years, it has significantly underperformed in terms of economic growth, so it has been difficult for it to be able to make the type of dramatic reductions in poverty that are required for social peace and stability.” The pattern suggests that poverty could take years to start falling and even longer to return to its pre-recession levels. This means that many families will need access to a safety net for many years to come. While not perfect, the Food Stamp Program has demonstrated its ability to respond quickly to changing economic circumstances. TANF has not. For a growing number of families, food stamps provide the only steady source of assistance to meet their basic needs. Food stamps cannot, however, pay the rent or utilities or pay for transportation to look for work or obtain needed medical care. The current recession has both highlighted the strengths and exposed critical weaknesses in the safety net. Federal and state policymakers should take what we have learned and begin to retool TANF and various other programs now both to better address current needs and to prepare for the uncertain future that lies ahead.

Unless Jamaica’s debt-to-GDP is significantly reduced, freeing up additional funds to further develop and grow its infrastructure, then the problem of poverty will continue. However, International aid and debt forgiveness has been pouring in and Jamaica is poised to becoming a developed country in 2030 and has achieved a number of its development goals. The Government of Jamaica, in collaboration with the private sector and civil society, has prepared a long-term National Development Plan: Vision 2030 Jamaica. The Plan envisages Jamaica reaching developed country status by 2030. It introduces a new paradigm, redefining the strategic direction. The old paradigm for generating prosperity was focused on exploiting the lower forms of capital – sun, sea and sand tourism – and exporting sub-soil assets and basic agricultural commodities. These “basic factors” cannot create the levels of prosperity required for sustained economic and social development. The new route is the development of the country’s higher forms of capital – the cultural, human, knowledge and institutional capital stocks – coupled with the reduction of inequality, which will move the society to higher stages of development.

”B. The Need for a workable and Sustainable-Sustainable Development Plan”

Neoliberal globalization has created income disparities within and across countries and regions and deepened the realities of poverty for marginalized and vulnerable peoples in the world. Poverty and Income Inequality are acceptable but up to a certain point according to the UN and economists, because poverty and inequality can cripple societies and create unwanted immigration as people flee to other countries, and chronic crime and violence which studies have correlated with poverty and income disparities. Almost all countries and peoples who experience poverty, and are at the bottom end of Globalization, are dealing with crime and violence, hunger and poor health. Communities such as Kensington Philadelphia, North Philadelphia, Detroit, Haiti, Jamaica etc., these places have one thing that is common, more black and brown peoples or poor peoples with low educational outcomes, poor health-rates and income disparities so that these places are experiencing higher levels of crimes and violence, and higher health-related issues compared to other places and peoples. Therefore, the UN has created a plan towards facilitating Sustainable development within and across countries and has set goals that is hinged on 10 benchmarks (2015-2030) based on the national and international needs and position of nations and peoples around the world.

Sustainable development recognizes that this can only be achieved by addressing global challenges in each country today, so as to preserve and position the future to continue to do so tomorrow. It is a type of structural adjustment, but it was supposed to be more humane and contextual speaking to the social and or human. For it is by building the human will society have the capabilities to utilize the capacities to effect change or to realize some goals. The issues most important were poverty, inequality, climate change, environmental degradation, peace, and justice. SA wasn’t effective because it was more top-down and made these developing, global south countries or marginal peoples more dependent and vulnerable to exogenous shocks. While the UN through its sustainable goals aimed to sustain development nations and peoples by empowering them; its other agencies (such as the IMF and WB and IADB) were working against that with SAPs that eventually deepened these countries dependence and exacerbated their debt. But with this new understanding, the UN has a new thrust, which is to engage the local so that there’s a broad-based approach to sustainability rather than top-down. Nevertheless, the UN have set certain benchmark goals which they hope to achieve by 2030. These include:

The 17 SDGs are: (1) No Poverty, (2) Zero Hunger, (3) Good Health and Well-being, (4) Quality Education, (5) Gender Equality, (6) Clean Water and Sanitation, (7) Affordable and Clean Energy, (8) Decent Work and Economic Growth, (9) Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure, (10) Reduced Inequality, (11) Sustainable Cities and Communities, (12) Responsible Consumption and Production, (13) Climate Action, (14) Life Below Water, (15) Life On Land, (16) Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions, (17) Partnerships for the Goals.

How effective is the UN’s SDG program? How realistic? How and what are the barriers: COVID, competition, SAPs, natural disasters etc.?

What are we doing to overcome those barriers? Strengthening Social Welfare Policies and Programs: This is where TANF and PATH supposed to do and policies were supposed to continue to evolve that would strengthen these programs to meet the changing economic situations in society and the world. In 2008 – 2012 we had the financial and housing crisis in the USA that not only affected the US but people in the global south who rely on remittances and aide from the US. Moreover, hurricanes, natural disasters and the COVID pandemic severely hampered the Caribbean and rolled back years of progress (see Neoliberalism, Globalization, Income Inequality, Poverty and Resistance.) The problem for vulnerable peoples and countries is their inability to maintain steady and upward growth; over the last several years their GDP has been unsteadied and uneven and these peoples constantly relies on aide. Further, many global south countries and people living in vulnerable and marginal communities are not as diversified in their economic activities, only relying on Tourism or certain revenue streams to generate revenues. Therefore, they may benefit from exploring ways to diversify their economy so that they can develop specializations and advantages in more than one or two goods or services, while strengthening their social welfare programs to increase their human capacity to meet the growing diversity and productivity.

What is social welfare in sustainable development? Social Welfare is one aspect of achieving sustainable development. Sustainable development is about strengthening a nation’s capacity to reach an acceptable level of development where that country can become interdependent (ability to provide for itself and citizens while meaningfully engaging and benefitting from international partnerships and trade). We had stated in previous chapters that Jamaica, for example has developed a PATH—Program through the Advancement of Health and Education. The aim of this program like other social programs aimed at alleviating poverty and enabling the capacities of peoples within its country that have limited resources and whose human capabilities can affect the overall sustainable development of a country in realizing self-sufficiency and interdependence. Similarly, in post-industrial or developed countries there are programs to help the poor and vulnerable. The Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program provides states and territories with flexibility in operating programs designed to help low-income families with children achieve economic self-sufficiency. States use TANF to fund monthly cash assistance payments to low-income families with children, as well as a wide range of service.

In order to get access to these programs, affected families with school aged children must meet certain requirements which have been developed in ideologies that are political instead of applying human sensitivities. In order to access these benefits families must enroll their school-aged children in school which is then used to determine benefits. In addition, there are work requirements and at one time TANF was a benefit (or the amount that each family or person received) that only certain unions or couples could access as it was tied to ideas about religion, faith and politics. It was the belief that social assistance encouraged poor people who benefit from social welfare and cash assistance to stay home and not work. But studies show that poor people want to work but the jobs that are available to them are low wage jobs that no one in society wants to do, and for these people they would rather live on welfare and take on ad-Hoc informal jobs so as to meaning survive as what TANF or PATH provides is barely enough to move people out of a cycle of poverty.

Further, I interviewed a consultant who has worked with Jamaica and the UN and UNDP and UNESCO studying the PATH program and exploring ways to improve the program while addressing barriers to realizing the UN 2030 SDG goals. According to Mr. Bradbury, PATH at its max it’s nearly not enough to allow any family to sustain themselves in Jamaica. Let alone develop themselves… it only maintains a level of poverty and dependency.

The Interview With Alvin Bradbury, Former Consultant at the Ministry of Education, Jamaica

——

On the issue of realizing the SDG goal of no poverty, the paper I presented analyzing and comparing social assistance with Jamaica and the USA suggested that poverty has been declining steadily since 2012. But since 2017, with COVID, poverty has risen and 10 percent of the world’s population live in poverty and struggle to meet basic needs such as health, education, and access to water and sanitation. Extreme poverty remains prevalent in low-income countries particularly those affected by conflict and political upheaval (sdg.un.org).

As it relates to Income Inequality, in 2015, more than half of the world’s 736 million people living in extreme poverty lived in Sub-Saharan Africa. Without a significant shift in social policy, extreme poverty will dramatically increase by 2030. In 73 countries during the period 2012–2017, the bottom 40 per cent of the population saw its incomes grow. Still, in all countries with data, the bottom 40 per cent of the population received less than 25 per cent of the overall income or consumption. Further, incomes may have risen, but this does not take into account inflation, rising prices and fall in interest rates, housing prices and other factors that affect incomes and its value. So incomes may have risen but the standards of living have also risen. So social welfare becomes very important in society to minimize this. But the desire and will to implement policies that effectively redistribute wealth and incomes and or to provide better services, benefits and adequate access to certain resources then, no UN goal will work. I’m fact, poverty and inequality has never been stable. For those who are its main citizens, poverty and incomes levels are fluid. It’s never constant. So, it would take bold steps and efforts which is not possible given human greed. The rich continue to get rich at the expense of the working class and social welfare is seen as suspicious. While we seek to develop how many are willing to now compete with another country. One must reconcile this competitive drive as well. 2030 is unreachable when countries are seeking economic dominance and competitive advantages over others. So, the UN sustainable development is a theoretical idea that is being exercised in futility and is antithetical to competition.

In fact, sustainable development is not new. This started in 1987 from a Report adopted from Scandinavia that recognizes the importance of building human capabilities and capacities so that we can respond to the challenges of tomorrow which the report suggests is climate change. If we can’t deal with the issues of today and position the future for tomorrow, the. There will be not tomorrow. So, over the years there have been efforts to develop plans to explore and implement programs that empower the human. But the results are not that positive given several world related health issues such as COVID, capitalist greed and unfair trading practices have all played a role in slowing any efforts for sustainable development across countries.

Please see End Notes below Reference List for additional information and comments.

== References ==

- Gordon, Derek, Class, Status, and Social Mobility in Jamaica (Institute of Social and Economic

Research, UWI, 1987)

2. Handa, Shudhanshu, and Damien King. “Structural Adjustment Policies, Income Distribution

and Poverty: A Review of the Jamaican Experience.” IDEAS: Economics and Finance

Research. World Development, 1997. Web. 05 Nov. 2010. Volume 24, No. 6, Pages 915

– 930<“http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/B6VC6-3SWY830

7/2/263e6f6011c57af1f434d2cbde359358”>.

3. Indicators of Welfare Dependence: Annual Report to Congress 2007, U.S. Department of Health

and Human Services

4. Jamaica, World Bank Data Report. “Income Share Held by Highest 20% | Data | Table.” Data |

TheWorldBank.Web.04Nov.2010. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.DST.05TH.20/countries>.

5. The Jamaica Gleaner Newspaper

6. The Jamaica Observer (http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/business/Poverty-alert-

Jamaica–region-facing-crisis_8661717#ixzz1QmzZWMXW)

7. Levy D. and J. Ohls. “Evaluation of Jamaica’s PATH Programme: Targeting Assessment.”

Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., July 2004.

8. Levy D. and J. Ohls. “Evaluation of Jamaica’s PATH Programme: Methodology Report.”

Washington, DC: Mathematica Policy Research, Inc., September 2003.

9. Lundy, Patricia, Debt and Adjustment: Social and Environmental Consequences in Jamaica

(Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 1999)

10. McKenzie, Renaldo C. Neoliberalism, Globalization, Income Inequality, Poverty and Resistance. Charlotte SC: Palmetto. 2021

11. Planning Institute of Jamaica/Statistical Institute of Jamaica “Survey of Living Conditions”

(1980 – 2010)

12. Randall, Vicky and Theobald, Robin, Political Change and Underdevelopment: A critical

Introduction to Third World Politics 2nd ed. (Durham: Duke University Press, 1998)

13. Scott, Liz and LaDonna Paretti. “Redesigning the TANF Contingency Fund to Make it More

Effective. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. June 13, 2011. http://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3512

14. Stone, Carl, Class Race and Political Behaviour in Urban Jamaica (Institute of Social and

Economic research, University of the West Indies, 1973)

15. World Bank Country Study, “The Road to Sustained Growth in Jamaica” (The World Bank,

2004)

16. www.moj.gov.jm/laws/statutes/Minimum%20Wage%20Act.pdf

17. The Employment Situation – January 2010, Bureau of Labor Statistics,

http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf.

18. The United Nations, Sustainable Development Goals 2015 – 2030. (Accessed from sdgs.un.org website via en.m.Wikipedia.org.)

End Notes:

- In Jamaica, Poverty fell from 20% in 2001 to 9.9% in 2009 and has risen again to 16.5% in 2010. In the US, poverty fell from 15.3% in 1993 to 12% in 2000 and it has risen since the global recession to 15.7% in 2011. Income inequality in both countries have either increased or remained the same measuring an average gini index of 0.45 over the last decade.

- From 1985 – 2000, the Caribbean since World War 2 has undergone significant economic policy transformation (Stallings, 2000). This has been the result of a ‘resurgence of liberalism’ (neo-liberalism) in the 1980s when the ‘right’ dominated the US-UK political landscape with the emergence of Reagan and Thatcher at the political helm, who promoted market deregulation and the expansion of neo-liberal activities and ideologies in the global north-south.

- The Jamaican government acquiesced to the “bureaucratic phenomenon” of the neo-liberals. They followed policies of structural adjustment which transformed its small political economy from social democracy and distributional equity to dependent capitalism in the1980s and market-capitalism in 1990s and 2000s.

- But this growth, Gordon suggest was at the expense of the lower classes (Gordon 1987, p.2). Hence those at the bottom of society experience further abject poverty and inequality.

- Real growth during the period averaged 5.2% and the middle class was expanded by from 25% of the population to 35%.

- He argued that they were ‘good’ years for Jamaica’s economy as it grew at a rapid rate averaging 5.8% p.a. (ibid, Pp. 5-6). Notwithstanding this, the economic fortunes were only felt among the upper classes which accounted for 5% of the population and poverty was at a high of 53%. The fact is, from 1958 – 1972, Inequality increased; the income of the bottom 40% fell from 8.2% to approximately 7% of aggregate income in 1971/2. Further, the windfall gains of the 50s and 60s were not restructured to develop the economy but focused on consumption. So by the 1970s, the new government was engaged on a policy of distributional equity and welfare, aimed at improving the plight of the poor and the lower classes.

- Hence government spending spiraled out of control, expanding the public sector and social programs, nationalized many private institutions and imposed market restrictions. This ‘socialist’ policy undermined economic development and neo-liberalism; the government had well-intentioned policies but neglected economic growth programs thinking that development occurs magically while draining the profits of the economy. The debt worsened and investment, aid and loans were difficult to ascertain given the socialist program which upset the neo-liberals with the capital. Hence, coupled with the oil crisis of the 70s and mass-migration Jamaica developed serious monetary and fiscal problems as it couldn’t meet its expenses and the government couldn’t pay its workers. Hence, they were forced to abandon social welfare and equity so that they could secure badly needed capital to pay its debt and workers and embark on long-term development.

- The expectation was that neo-liberal policies of ‘Structural Adjustment’ which included the privatization of public enterprises, removal of price controls and removal of trade restrictions, would speed up economic growth, increase productivity and lead to job creation and even greater equity as overtime economic growth should lead to economic equality which Kuznets et al has theorized. On the other hand, from 1985 – 2005, Jamaica’s economic growth has been very slow/flat and employment in the formal sector decreased and the debt has worsened, while poverty and Inequality have declined.

- Jamaica has arable land for farming, outstanding scenic beauty, and high levels of biodiversity, white sand beaches and modest mineral resources. These provided for much of the early income growth generated from a vibrant tourist industry, sugar, bananas and significant bauxite mining. Today the sugar and banana industries are in decline, partly due to the ending of trade preferences with Britain as a result of the NAFT agreement signed by President Clinton. Jamaica’s tourist industry has strengthened and is of a high standard, attracting 2.9 million visitors a year. Its bauxite industry has, until recently, been expanding. Overall, unemployment has declined from 15% in 1990 to 10.6% in 2008. This decrease is partly due to the growth of the informal sector from an estimated 28% of GDP in 1989 to an estimated 43% in 2001, probably one of the several contributors to a significant reduction in poverty levels.

- Real gross domestic product grew by only 0.8% per annum from 1973 to 2007, although in the last decade it has been 1.3%.5 Remittances from the Jamaican Diaspora have been escalating, and are now the country’s leading source of foreign exchange totaling over US$2B in 2008.

- The country is heavily indebted and with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 111.3% (2007) has the fourth highest ratio in the world. In the latest 2009/10 budget, debt servicing (56.5%) and wages and salaries for civil servants (22.5%) left very limited fiscal space for development priorities such as infrastructure and social program. Education received 12.6%, national security 8.2% and health 5.3%. It is important to note that the debt includes the sum absorbed by the Jamaican government in the wake of the financial sector crisis of 1995-96, amounting to 44% of GDP. Most of the resultant debt is held by local creditors, and was 53.7% of total debt in January 2009. Since the crisis, more stringent monitoring and regulation of the financial sector has been introduced.

- Additionally, Jamaica is highly vulnerable to hurricanes, flooding, and earthquakes. In a 2005 World Bank ranking of natural disaster hotspots Jamaica ranked third among 75 countries with two or more hazards, with 95% of its total area at risk.10 Between 2004 and 2008, five major events caused damage and losses estimated at US$1.2B. These have had significant impact on human welfare, economic activities, infrastructure, property losses and natural resources. Outbreaks of dengue and leptospirosis experienced in 2007 were largely influenced by weather conditions. And crime has compounded Jamaica’s problems as 60 per 100,000 persons in 2008 were murdered as Jamaica wrestle with its high crime-rate, which is one of the worse in the world. Its characteristics are male on male, poor on poor, and youth on youth. Half of those admitted to high security adult correctional centers for major crimes in 2007 were males between 17 and 30 years of age. The ratio of males to females who commit major crimes is 49:1. Seventy-seven percent of murders in 2008 were committed using guns. Jamaica has become a trans-shipment point between the USA and South America and this gun trade has increased their availability, facilitated by drug profits. The cost of crime and violence is undoubtedly a factor in Jamaica’s stagnant growth. A World Bank Study conducted in 2002, found the cost of crime and violence in 2001 to be 3.7% of GDP.

- The global recession is now having a significant impact on the Jamaican economy. Falling demand for alumina on the world market has resulted in the closure of major bauxite operations for at least one year, resulting in 1,850 job losses, another 850 jobs taking a 40% salary cut from a shorter work week, and a predicted 70% decline in bauxite revenues for the next financial year. There were 14,750 job losses from other sectors between October 2008 and May 2009.6 From November 2008 to February 2009, remittances, which have been increasing every year for a decade, were down by 21%. Up to the end of February 2009 tourist arrivals had continued to increase but earnings were down due to heavy discounting. Arrivals and average expenditure per visitor are expected to decline in the future. Inflation is increasing: the Jamaican dollar devalued against the US$ by 22% from September 2008 to mid-February 2009. The social impact of the crisis has not yet been documented, but already property crimes are reported by the police to be increasing markedly island wide. Remittances, tourism, and bauxite together account for over 85% of Jamaica’s foreign exchange.

- For instance: “Education was widely associated with high well-being and so it seemed reasonable to infer that schools are regarded as important because of the personal benefits that are seen to accrue from investing in education. In this vein, the costs of buying into education service were seen as a major impediment to social advancement by the poorer groups” (The World Bank 2001b, p. 43).

- For instance, immunization rates for infants up to 11 months of age fell from 93 percent in 1993 to 85 percent in 1999 (The World Bank 2001c). While children are often immunized by the time they start primary school, they are not necessarily immunized early enough. Inadequate prenatal care has also been a serious problem.

- Case in point, the poor perceive public health centers in rural areas, though not easily accessible to many communities, as highly important because private clinics charge far higher consultation fees (The World Bank 2001b). Both preventive and ameliorative programs are necessary for improving the health of youth, pregnant and lactating women, the elderly, and the disabled. For youth, preventive programs, which ought to begin during the early childhood development stage, should lay the foundation for better developmental outcomes and lead to high returns later in life. For adults, regular checkups should improve individuals’ health and chronic illness monitoring and reduce emergency visits.

- The Gini coefficient moved from 0.367 in 1992 to 0.45 in 2009.

- Among the 14.8 million unemployed in January 2010 were 6.3 million persons who had been unemployed for 27 weeks or longer. The unemployment rates for African American and Hispanic workers were significantly higher than for the total population, at 16.5 and 12.6 percent, respectively. And teenagers faced an unemployment rate more than two and a half times the national rate: 26.4 percent. Source: The Employment Situation – January 2010, Bureau of Labor Statistics, http://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf.

- Including three income support programs – the Food Stamps Program, Poor Relief Program, and Public Assistance Program—four school-based programs, five labor market program, two subsidized drug programs, and an indigent housing program, among others.

- For example, approximately 263,000 persons registered to receive food stamps in 1998. However, less than 30 percent of the households receiving food stamps fell into the poorest quintile (Blank 2001). These government programs provided low benefit levels offer less-than-adequate support, which, given the cost of obtaining benefits, probably deters eligible individuals from even applying for benefits.

- [1] To participate in the program, a household must apply to its MLSS parish office, providing detailed information about its demographic and socio-economic characteristics in order to allow MLSS to calculate a score on a scale used to determine eligibility. The information is then data entered into a management information system (MIS) at the central MLSS offices, and the household is notified of the eligibility determination. In general, home interviews are not conducted unless there is a specific reason to do so. The bimonthly benefits are disbursed through local post offices.

- The receipt of health grants is conditioned on children through age 6 (not enrolled in school) visiting a health clinic (every two months during the first year and twice a year thereafter). The receipt of education grants is conditioned on regular school attendance (at least 85 percent of school days) by poor children age 6 through 17. Each child in the household is eligible to receive only one type of grant: health (if age 0 to 5) or education (if aged 6 to 17).

- As a reference, the minimum wage in Jamaica for general workers is currently about US$160 per month Economic and Social Survey of Jamaica, 2005). A household receives a monthly grant amount based on the number of eligible members. Hence, a household with two children eligible for the health grant, two children eligible for the education grant, and one eligible adult would receive US$32.50 per month in the first year (i.e., five eligible persons multiplied by US$6.50). Another important benefit for many PATH households was the government’s waiver or payment of certain education and health fees. Such fees covered the annual tuition fee that students must pay, and the cost of a visit to a health center.

- The average monthly benefit per person is the same as the benefit in the child assistance grants.

- The four purposes of TANF are: (1) assisting needy families so that children can be cared for in their own homes; (2) reducing the dependency of needy parents by promoting job preparation, work, and marriage; (3) preventing out-of-wedlock pregnancies; and (4) encouraging the formation and maintenance of two-parent families.

- Cash grants vary widely — the maximum monthly benefit for a family of three with no income ranges from $170 in Mississippi to $923 in Alaska — and only about half the states (26) provide a maximum monthly benefit of at least $400, which is about 20 percent of the poverty line.

- Indicators of Welfare Dependence: Annual Report to Congress 2007, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, http://www.mathematica-mpr.com/publications/PDFs/family_support/TANF_caseloads.pdf.

- [1] This represents 12% of the population, 70% children and 11% elderly. Benefits are received based on compliance with educational and health requirement. In 2004 about 245000 individuals applied for PATH, 180,000 received benefits. Benefits are received based on compliance with education and health requirements. PATH’s Targeting Report, Mathematica Policy Research, June, 2004.

- PATH has increased school attendance by approximately 0.5 days per month. The estimated increase is about 3 percent in 2004.

- The results of the statistical analysis suggest that health care visits for children 0-6 years old increased by approximately 38 percent as a result of PATH.

- We note here some problems with implementation: 1. there are often delays in making PATH payments available to clients. The resulting uncertainty about the timing of benefit availability imposes substantial costs and sometimes hardships on clients. 2. Many stakeholders, including both clients and also workers at schools and health clinics, believe that there are problems in the accuracy of the information used for enforcing the sanctions. related to school and health care requirements. There appear to be particular issues in getting medical excuses for school absences reflected in the system and in dealing with situations where clients use a health care facility other than the one they typically use. 3 Difficulties and delays in obtaining information from MLSS representatives about their cases and in having changes made in their case records These and similar issues warrant review by Jamaica officials to ensure that PATH policies are being implemented as completely as possible.

- These include the Poor Relief, the School Fee Assistance Program (SFAP), and the Jamaica Drugs for the Elderly Programme (JaDEP).

- However, the state variation is significant. In ten states, caseloads actually declined or remained flat; in 13 others, caseloads increased by 1 to 5 percent. Caseloads responded moderately in 12 states, increasing by between 6 and 15 percent. Caseloads increased by more than 15 percent in 16 states. New Hampshire, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, and Oregon led the way, with increases of 38, 38, 37, 36, and 34 percent, respectively. However, New Hampshire and Utah started from a very small base, having had large declines in their TANF caseloads a few years before the recession started. Most states that experienced significant increases in their TANF caseloads also had above-average increases in their food stamp caseloads.

- However, the state variation is significant. In ten states, caseloads actually declined or remained flat; in 13 others, caseloads increased by 1 to 5 percent. Caseloads responded moderately in 12 states, increasing by between 6 and 15 percent. Caseloads increased by more than 15 percent in 16 states. New Hampshire, New Mexico, Utah, Colorado, and Oregon led the way, with increases of 38, 38, 37, 36, and 34 percent, respectively. However, New Hampshire and Utah started from a very small base, having had large declines in their TANF caseloads a few years before the recession started. Most states that experienced significant increases in their TANF caseloads also had above-average increases in their food stamp caseload (http://www.jamaicaobserver.com/business/Poverty-alert—Jamaica–region-facing-crisis_8661717#ixzz1QmzZWMXW)

Revised Article Published and copywrighted by by The Neoliberal Corporation/ Renaldocmckenzie, April, 2022.

Contact - The Neoliberal (renaldocmckenzie.com)