The abolition of slavery in the West Indies in 1833 marked a significant milestone in the fight against human bondage. However, the news of emancipation did not reach the enslaved population until 1865, leaving them to toil as free laborers for over three decades without compensation. This essay delves into the profound injustice endured by these individuals and examines the question of why their emancipation went unrecognized for so long. Furthermore, it explores the implications of this delayed freedom, the potential for lost wages and forced labor, and the need for compensation and remuneration for their toil.

Historical Context

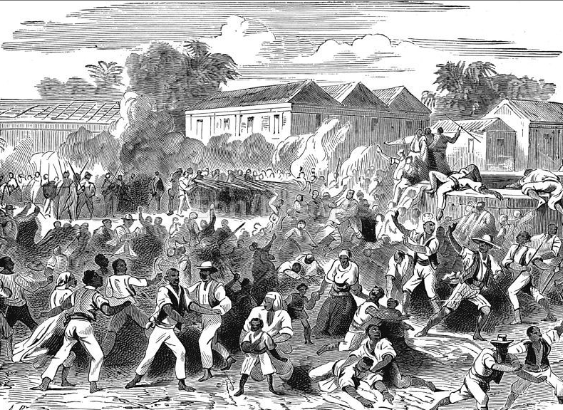

Between 1833 and 1865, blacks working as slaves on plantations in the West Indies were technically freed, but they were unaware of their emancipation for over 32 years. This startling revelation raises crucial questions about the responsibility of plantation owners, the government, and the dominant class in compensating these individuals for their labor during this extended period. While the insurance claims made by plantation owners against the loss of property due to the abolition of slavery were honored, the compensation owed to the workers themselves was neglected.

Compensation for Lost Wages

In Fact, in an article entitled: Unmasking slavery’s profiteers, published in the Jamaica Gleaner’s Editorial on Sunday August 4, 2013, Historians Verene Shepherd, Ahmed Reid, Daive Dunkley and Dave Gosse, guest columnists argued and provided evidence of the estimated dollar amount of insurance claims and compensation received by enslavers in the commonwealth. However, their research did not uncover any compensation to the freed slaves. According to the editorial:

- The exploitation of enslaved Africans and the transatlantic slave trade played a crucial role in Britain’s rise as an industrial superpower. historian and the late prime minister of Trinidad and Tobago, Eric Williams, published Capitalism and Slavery in 1944, he argued that the transatlantic trade in Africans and plantation slavery provided the impetus for Britain’s industrial advancement.

- The wealth generated from slavery was invested and reinvested in various sectors of British society, including railroads, shipbuilding, insurance, the financial sector, the arts, and shopkeeping.

- The decision to abolish slavery in 1833 had a significant financial impact on those who had invested capital in slavery and the plantation system. To soften the blow, the British government provided a £20 million bailout to enslavers, representing 40% of British public expenditure at the time.

- The Compensation Claims, which were filed by enslavers to receive compensation for their loss of enslaved people, provide valuable data for understanding the ownership of enslaved people during the transition from slavery to freedom.

- The compensation records reveal that more than half of the £20 million paid in compensation stayed in Britain and was reinvested in various sectors such as the financial sector, railroads, and cultural institutions.

- While many enslavers were absentees living in Britain, Jamaica had a significant population of resident enslavers who also filed claims and received substantial compensation.

- Preliminary findings show that 16,114 claims were filed for enslaved people in Jamaica, with the majority filed by resident enslavers. The total compensation received by resident enslavers amounted to £4.10 million.

If the plantocracy and the enslavers received compensation for their loss of property, it stands to reason that the workers who toiled on the plantations during the period of delayed emancipation should be entitled to compensation for their loss of wages and forced labor. The legal and moral obligation to acknowledge their unpaid labor and provide restitution is a matter of social justice. The intergenerational impact of this injustice cannot be ignored, as the descendants of these freed slaves also suffered economically as a result.

Delayed Emancipation: Motives and Implications

The delayed transmission of news regarding emancipation begs the question: Why did it take so long for the slaves’ liberation to be known? It is possible that the dominant class, consisting of the plantocracy, crown, and government, deliberately withheld this information to mitigate potential losses and adequately prepare for the transition from slave labor to alternative forms of exploitation. The decision to end slavery necessitated a carefully orchestrated process, which included the establishment of indentured labor systems using bonded servants from China and India. This transformation from chattel slavery to indentured servitude reduced the plantation owners’ responsibility to provide for the welfare of the workers, ultimately resulting in lowered labor costs.

Post-Emancipation Economic Realities

With the advent of automation and scientific advancements in production, slavery was no longer the most profitable labor system. The plantocracy gradually transitioned from slave labor to indentured and then chattel and wage labor, benefitting economically from these changes. However, the formerly enslaved individuals never experienced economic recovery. They left the plantations without any form of compensation, benefits, or remuneration, with their welfare disregarded by the dominant class. The long-term economic ramifications of this systemic neglect continue to be felt by their descendants, perpetuating cycles of poverty and inequality.

Conclusion

The delayed emancipation and subsequent denial of compensation for over three decades of free labor endured by the West Indian slaves reveal a dark chapter in history that demands redress. The legacy of slavery continues to shape social and economic disparities in the region, with the descendants of the formerly enslaved still grappling with the aftermath of unpaid toil and systemic neglect. Recognizing the historical injustice and advocating for compensation and remuneration for the affected individuals and their descendants is not only a matter of restitution but also a step towards rectifying the enduring imbalances rooted in West Indian history. It is time to confront this painful past and forge a path toward a more just and equitable future for all.

Author: Rev. Renaldo McKenzie

Biography: Rev. Renaldo McKenzie is an esteemed Adjunct Professor at Jamaica Theological Seminary. With a deep passion for social justice and economic equality, he has dedicated his career to exploring the intersection of neoliberalism, globalization, income inequality, poverty, and resistance, the tile of his first book. As an author, his insightful works shed light on the pressing issues faced by marginalized communities. Rev. McKenzie’s expertise and advocacy for equitable policies have made him a leading voice in the ongoing dialogue on social and economic justice.

Contact Renaldo at: Email: Website: renaldocmckenzie.com

Reference

- Verene Shepherd, Ahmed Reid, Daive Dunkley and Dave Gosse, Unmasking slavery’s profiteers. Kingston: Jamaica Gleaner. August 4, 2013.

- McKenzie, Renaldo and Martin Oppenheimer. NeoLiberal Globalization Reconsidered, Neo-Capitalism and the Death of Nations (In review).

Note: This post was first published in The NeoLiberal Post and was submitted to the Jamaica Gleaner Letters and The Jacobin Magazine as a letter to be considered for publication. This article is being developed in a study/research.

Donate to The NeoLiberal Corporation Growth Fund:

Visit our Bookstores and Resources Centers:

Error: Contact form not found.