Preface to Neoliberalism…

When we hear of Jamaica or the Caribbean, we think of beautiful islands of paradise with sun, sea and sand, reggae music, cannabis, and “irie” people like Usain Bolt— people who are living out their best dreams, desires, and lives. But this book analyzes this motif, given the historical and current economic and political situation in Jamaica and the Caribbean and the “Global South.”

In an attempt to escape the adverse realities of pov-erty, inequality, and injustice, the people of the Global South find themselves in north metropolises with very little agency and minimal change to their lives. In fact, except for the use of cleaning neoliberal waste, the immigrant is usually portrayed as an alien with three heads and big sharp teeth seeking to steal and destroy the profit and disrupt society. As such we will discuss Black, brown, and Pan-African struggles for economic prosperity, justice, and freedom and consider efforts, abilities, or inabilities to chart their own futures since decolonization and realize real political independence and economic prosperity. Perhaps, they are charting their own course by the few corrupt of the status quo who are benefiting from partnerships with the neoliber- al regime of the “Washington Consensus,” advocates of the “bureaucratic phenomenon,” while the masses are left behind. John Williamson, the inventor of the term “Washington Consensus,” believes the term has two quite different meanings. First is the meaning he gave the term, which involved consensus around a set of ten policy reforms, which he believed were widely accepted as beneficial by economists. In the original formulation, these were:

(i) fiscal discipline; (ii) a redirection of public expenditure priorities toward fields offering both high economic returns and the potential to improve income distribution, such as primary health care, primary education, and infrastructure; (iii) tax reform (to lower marginal rates and broaden the tax base); (iv) interest rate liberalization; (v) a competitive exchange rate; (vi) trade liberalization; (vii) liberalization of FDI inflows; (viii) privatization; (ix) deregulation (in the sense of abolishing barriers to entry and exit); and (x) secure property rights. Second is the meaning the term has acquired: market fundamentalism or [neoliberalism]: laissezfaire, Reaganomics, let us bash the state, the markets will resolve everything.

For our examination, we will use the term in the latter, rather than the former common, usage to denote the power dynamic at play in neoliberal globalization and neoliberalism. The approach will be interdisciplinary and comprehensive, drawing on various disciplines and expe- riences and going beyond Jamaica to consider the wider Caribbean and the diaspora in the United States. It draws on past and present works on the subject and relies on readers’ abilities, knowledge (primary or secondary), and skills to challenge, critically analyze, and develop their own thinking within a Jamaican, Caribbean, its di- aspora, and/or American context given this century’s challenges and opportunities. This book is facilitatory, as it another opportunity to holistically explore challeng- es, opportunities, and solutions to Caribbean and Pan- African problems, so they can continue to develop and express these thoughts in a structured, creative way that is unique to them, one that will lead toward meaning- ful engagements and sustained improvements for them and their people’s standards of living. This project is divided into two parts.

Part A will examine whether Jamaica’s inequality trends from the mid-1970s up to the beginning of the twenty-first century were a consequence of the structural adjustment policies stipulated by the neoliberal technocrats of the Washington Consensus in Jamaica. The study does not only concern itself with Jamaica, but Jamaica provides a case and a context within which to enagage the sub- ject matter. We will attempt to do so by tracing the im- pact of “structural adjustment” on Jamaica’s economy and the relationship to this on income inequality and poverty in Jamaica from 1960s to 2008, with updated 2020 figures. We will argue that, given the premise, Jamaica presents a unique cause-and-effect scenario that continues to question the veracity and validity of the premise that neoliberalism is the sine qua non of de- velopment. We will explore and compare Jamaica with other Caribbean contexts and consider situations that are similar to these contexts in the diaspora in the United States, whose people in the inner cities are also reeling from the effects of neoliberal globalization. For consid- eration of this study, which began in 2010, I must admit that I am biased by my own experiences as a postcolo- nial man living in a postindustrial country or superpow- er, the USA. What voice do I have, if any, and what are the threats to that voice? We will consider Caribbean and Pan-African contexts and thinkers such as Fanon and his contemporaries, who have questioned whether Jamaica and other Caribbean and former colonies and their people are free of external control and power. We will argue that this illusion of freedom comes from a dominant globalist worldview within which those in the Global South find themselves competing not just for “scarce benefits and spoils” but against two dominant forces vying for control—East versus West, Marxist/so- cialist ideology versus capitalist, Adam Smith, Keynesian free-market principle. We will conclude by considering whether any lessons have been learned by Jamaica and explore alternatives and solutions.

Part B will argue, given Jamaica’s experience with neoliberal restructuring, that Jamaica—like many former colonies—is far from independent. Since post–World War II, the Caribbean has undergone significant economic policy transformation. This has been the result of a re- surgence of liberalism (in its new form of neoliberalism) in the 1980s when the political right dominated the US- UK political landscape with the emergence of Reagan and Thatcher at the political helm. Both promoted mar- ket deregulation and the expansion of neoliberal activi- ties and ideologies in the Global North-South.2 The fact is that decolonization and neoliberal globalization have deepened Jamaica’s dependence on the new global elite of the Washington Consensus. We will explore how Fanon’s ideas apply to the de- and recolonization and neoliberal globalization experience of Jamaica. My own observations are oriented by my interest in the political economy of decolonization and neoliberal globalization. Further, we will consider the response to the pro- cesses of decolonization and globalization that have deepened the realities of the peoples of the Global South and the peoples in the diaspora. There have been hundreds of protests against the Washington Consensus and their lackeys since 1976 by the global justice move- ment and recently the Black Lives Matter movement in America. Street protests and some degree of violence have been the main strategies of the group until recent- ly. But are the resistance movements closer to achiev- ing their aims? The effectiveness of the resistance will be determined by the extent to which they have real- ized actual power: “demonstrated change in the desired direction.”

Essentially, we are interested in exploring, by virtue of good reason, whether actions of resis- tance have had any meaningful effect on the daily lives of the poor and marginalized peoples in countries like Jamaica and its diaspora in the United States. How close is the global justice movement is to achieving its demands, such as tax on speculative capital flows; radical education of developing world debt; poverty, food and water security, economic equity; and international justice and peace. Geoffrey Pleyers observes that the movement is in no way closer to realizing its goals and that the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has made structural adjustment (SA) sound nicer by calling it “poverty reduction.”5 Further, today almost half the world’s population (over 3 billion people) lives on less than US$2.50 a day. The gross domestic product (GDP) of the forty-one heavily indebted poor countries (567 million people) is less than the wealth of the world’s seven richest people combined. Poverty is virtually un- changed since 1981, and inequality remains unchecked and is rising. The middle or working class (whatever the designation for poor, wage-dependent classes of people) is shrinking, thereby creating a society of only rich and poor people, an observation shared by Marty Oppenheimer, former professor of sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. There is no middle class anymore: you are either part of the working class or the upper class.

Moreover, there has been significant decline in the membership and viewership of the resistance and or global justice movements since their inception. There have been several failed events, and the aforementioned movements have been very reluctant in responding to injustice and new strategies of neoliberal exploitation.

We will critique the work of nationalists to bring about political independence and equity within and among nations and peoples of the Global South, including those in the diaspora. For when nationalists speak in the name of the working class, they leave the impression of promoting a working-class political agenda. However, their project does not sway from elitism, and they never see beyond capitalism. They may imagine ways to re- duce foreign penetration, domination, and what passes for “cultural imperialism”; however, this stance reinforces capitalist class relations and bourgeois ideology while it fails to benefit the working class in any fundamen- tal way. We will explore these limitations and consider possible alternatives. We will conclude this section by discussing the recent Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests in American cities against economic discrimination and police violence and lift up some stories that resulted from that recent event. We will include some discourse that emanated from the BLM protests for our examina- tion on neoliberalism, globalization, income inequality, poverty, and resistance.

Finally, we will conclude with two essays that explore resistance through cinema: “Cinema and Globalization.” The recent BLM protests and the history of global justice movements have been met with fierce opposition even by their own citizens and people’s, albeit of a different class, race, or geographic region. This continues to re- veal the ease of blinding people to neoliberal globaliza- tion’s harsh effects. Human suffering is invisible to the human eye, and cinema has been used to tell the truth about globalization to the unsuspecting Westerner and to move people to act differently toward their plight and to consider deeply our human condition and position. We will examine and analyze two notable films, Life and Debt and Dirty Pretty Things, that will situate and con- clude our discussions in a cinematic view.

The Neoliberal Corporation Serving the world today to solve tomorrow’s challenges

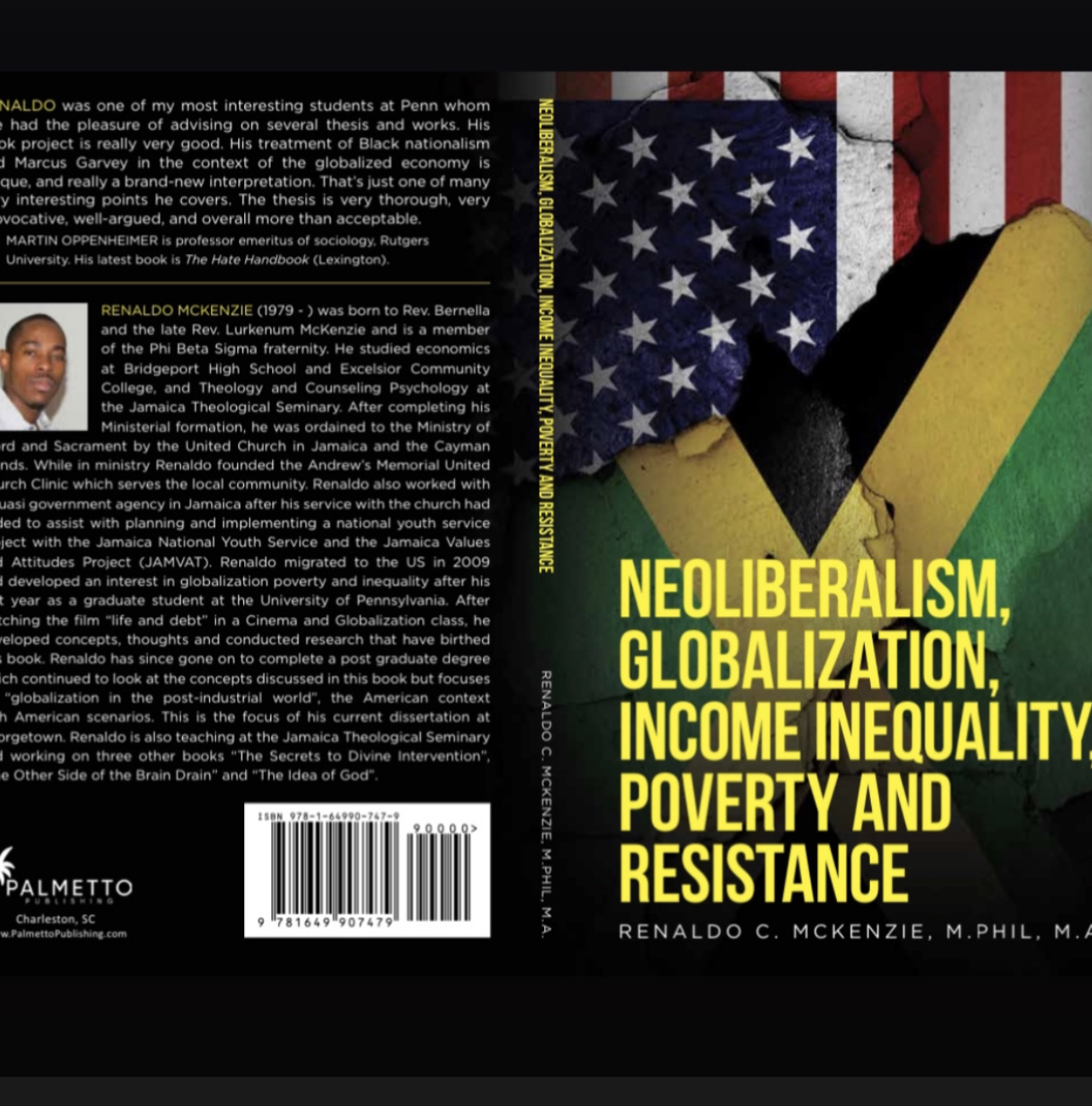

Preface of the Upcoming Book: Neoliberalism Globalization Income Inequality Poverty and Resistance, by Rev. Renaldo C. McKenzie, M.Phil, M.A, Doctoral Candidate at Georgetown University. http://linkedin.com/in/renaldo-mckenzie-rev-m-phil-m-a-08724944 Continue to check our website for updated on order and release details. Follow on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/theneoliberalcorporation/ and LinkedIn at http://linkedin.com/in/the-neoliberal-corporation-545b6720b

The NeoLiberal Corporation. Contact us at [email protected]